Columnists

The first prescription

One recent afternoon I had tea with Ernie Margetson as he guided me book by book through a collection of old volumes. Ernie is a multi-disciplined professional steeped in the history and lore of the County. As architect engineer, I have come to call him the house whisperer. Set Ernie on an old property with house and outbuildings and he will thread the story of when; why; and likely which family brought a certain place into being. He will further that by describing the likely eras of alterations undertaken since the foundations of that property were originally laid.

The books Ernie had in his possession had been rescued by his father, Ralph, during a past mid-century time of the clearing out of one-room schoolhouses. Built c1900, the County/Board of Education facilities were being closed. Along with the books many of the artefacts—furniture, stoves, teaching supplies even the name plaques identifying the institutions with their S.S. number—became swallowed up into the community at large or ended as landfill.

Shuttering the County’s original places of learning was in line with efforts to transform and amalgamate the then remote classrooms by building new, centralized facilities the likes of CML Snider Public School in Wellington and the later Queen Elizabeth School in Picton. During our current watch, the story in the news is how many of these past examples of modernizing are now also being closed to facilitate ‘modern modernizing’.

Also, over the course of time, several desanctified church buildings joined in a fade into history. Within our landscape today several of these places of learning or worship remain in various conditions that range from the unrecognizably altered to beautifully reconditioned and repurposed structures cum residence, workplace or simply sites wide open to imaginative contemporary purpose. Wherever and whatever their original intent, these heritage builds are bookmarks, trail markers that bring together stories from before. Often they are links to now vanished but once thriving hamlets and villages throughout the County. Thinking out loud, maybe that reminisce can lead to a map of the ‘once was’ or the ‘relic trail’ and another out loud is to ponder how the influence of the current pandemic will have on domestic and commercial architecture going forward.

Ernie and I sat perched on a long wooden bench in his barn as afternoon sunlight reached into the shadows and landed on the dog-eared cardboard box of bound literature. The cache had been passed down from dad to son, and son Ernie continues to hang onto the editions, revering them as booty of County collective memory. “It’s my appreciation of those books, how they were made, where they came from, and the fingerprints on them of those before us that makes them so appealing to me,” Ernie told me. “And it’s why I kept them” he furthered.

We talked about the various dates of the publications, and in many cases reflected on the scope of subjects that were being covered at the time. On the inside cover of each book was a pen and ink inscription indicating which book belonged to which school. Ernie gestured to two volumes in my hand. “They were from school sections in Hillier (Township). School section (SS) number 2, and number 7” he said. In many cases, following graduation at a Grade Eight level, students were called to duty on the farm; continuing education was then through self-motivation while gaining handson skills and know-how handed down through family generations was utmost.

What struck me about Ernie’s collection was the range of literary works that were included in teaching programs being advanced in classrooms of varying grades. Thoughts turned to how a range of ages were enabled to learn from the whole. Titles ran through a list of authors from Dickens to William Blake to Edith Nesbit, almost all were published in Britain or the U.S. as Canada was still very much under the sway of old world cultural influences. Exposure to our home-grown voices in the arts was in the making. As part of that transition, one person would play a role in tying together art, history and practical illustration to bridge a series of curriculums. His name was Charles William Jefferys.

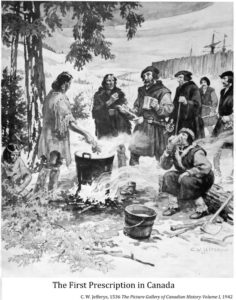

While the Canadian landscape was a favoured subject, C.W. Jefferys, as his signature came to be known, produced fundamentally accurate depictions and illustrations of early Canadian life and events that continue to inform us today. Born in England in 1869, as a child, Jefferys immigrated with his family to Philadelphia before moving to Toronto around 1878. As a teenager, Jefferys apprenticed with a lithography firm and studied oil painting with George A. Reid and watercolour with C. M. Manly. “It is inevitable that a country with such marked physical characteristics as Canada possesses should impress itself forcefully upon our artists,” Jefferys is quoted as saying.

In 1892, he moved to the United States and became an artist reporter for the New York Herald. In the precamera era, depicting a scene was rendered by the hand of an illustrator. While covering the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, Jefferys encountered Scandinavian painting. He, like other Canadian artists of his time, would be struck by the clarity and sharpness of the light captured in these works. Later this would be translated through his affection for the prairie landscape, but over the course of the following decades it would be Jefferys’ illustrated publications, including The Makers of Canada (1911), Chronicles of Canada (1914–1916) and A Picture Gallery of Canadian History (1942–1950) that were most valued.

After leaving Ernie’s place that recent afternoon, I was prompted to look for two of those listed volumes I have on my shelf. If you look up Jefferys’ work on the Internet you will experience what unfolds as a storyboard of Canadian history. Some of it perhaps over dramatized, but most of it vivid stamps of the past—the good, bad and the ugly. In looking at a string of his images, a theme of hubris on the part of early arrivals feels apparent. You will also see listed recent events at the high school in north Toronto named for Jefferys that has rebounded from tragedy to set examples for others. But most of all what prompted me to re-think Jefferys was one of his illustrations – The First Prescription—that seemed to jump off the sheet of one book in Ernie’s collection. I have included it on this page. It remains as a poignant message that was once included in school books of the past. So where is it now?

Comments (0)