walkingwiththunder.com

Visual notations

It was the artist who offered hand drawn records of pre-camera events; they were integral to any exploration crew and in the military, recognition and development of drawing skills were all important to the ranks and strategists in defining terrain and placements.

Of my favourite early colonists painters in Canada who have left us a treasure trove of work depicting First Nations communities and the era of the fur trade there are two: Frances Anne Beechy was born in England and in 1858 she married Edward Hopkins who had a role in the Hudson Bay Company. When he was assigned to Canada they travelled together along the routes from Montreal to Fort William on Lake Superior. Her paintings documented the labours and journeys of the voyageurs who were their cargo-canoe wilderness chauffeurs. The voyageurs in turn had learned the craft of canoe building and navigation from First Peoples.

Of the same era, living in then York (Toronto), Paul Kane was an Irish-born Canadian painter who persuaded the HBC to sponsor him to travel beyond the lakehead in order to paint. He would become known for his depictions and note taking of Native Americans in the Canadian West and in the Columbia District. His detail work has enabled many an interpreter of history to fathom the unity and practices of early societies.

Later in the 1800s with thanks to the invention of the camera and especially those who made effort to capture respective times, we are left with additional records of eras gone by. Photo equipment was elaborate and often required an assistant to help move about especially when out of the studio. I sometimes feel that earlier paintings and photos are also messages in a bottle, one generation sending visual information forward to future generations stating, this is what went on, these were the people and importantly this is what the place looked like and what we saw on our watch.

In my work as a filmmaker, I have had the opportunity to scan the archives of many places across the country. Wearing light cotton gloves to protect the images from residue, there is a Pandora’s Box to be opened by examining one image after another, sometimes using a magnifying glass to pick out details. While the insight is not intended to be about nostalgia, it becomes that when we get a sense of the bones of a place, the streetscapes and urban blueprint that has evolved from the colonial era through to the present. From time captured we’re able to see how a place has changed; we better understand architectural influences that, similar to all threads of society, were stuffed in the baggage of our ancestors as they travelled across the seas.

By example, the Greek revival style of buildings with the symmetry of high columns symbolizing grandeur and authority continues in influence since 447 BC and the building of the Parthenon in Greece. By contrast the log cabin of eastern North America or the sod houses of the west became the symbol of early European footprints on lands then occupied by vast, aboriginal civilizations. The paradigms of societal hierarchy—what was already known and popularly accepted—also came with personal belongings.

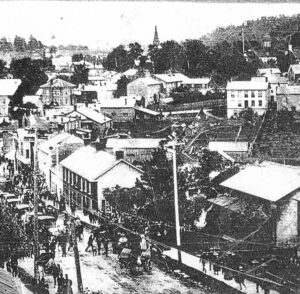

The photo here of Picton hill offers much by way of description of community. Historically, the highest elevations in a setting were reserved for clergy; next came the rule of earthly law as witnessed with the placement of the Greek revival courthouse in then Hallowell. (top right); then followed industry, traditionally centered around water power or as in this image, trade and travel as witnessed by the bustle on the hill when a steamboat has just arrived in the harbour. The Picton side of the bay, where the camera is placed, would eventually win out in the rivalry of the two communities mainly because the landscape offered a plateau where rows of buildings bordering a Main Street became the centre of day-to-day commerce.

I’m guessing the era to be c1890, evidenced by the electricity poles; all of the vehicles are horse-drawn. The camera is likely on the roof of a two-storey brick building that once sat directly at the top of the northeast corner of the hill. The edifice once housed the original law practice of our first prime minister, Sir John A. The camera is pointed eastward toward Hallowell. Extending horizontally across the middle of the photo is an elongated building that once was the barrel making operation of the Reid Brothers. Believing the operation to have originally started out in Ameliasburgh, the large, Irish born Reid family were invited to establish a cooperage on the harbour.

Interesting here is that ships and barges could navigate beyond Bridge Street at the tip of the bay and through a draw bridge enabling them to dock alongside the row of buildings. The watershed was navigable upstream beyond York Street and towards Glenwood cemetery. In the 1900s, the area became the town dump where ironically, according to the chronicles of the late Willis Metcalfe, two wooden sailing vessels were towed to their final resting place and now lie beneath the soil. From a land impact standpoint, since colonial times the creek and surrounding wetlands have been reduced almost to beyond recognition.

In terms of the domestic scene, wealth was expressed by the number of panes of glass and the number of windows in a house as glass was a rare commodity in earlier times. Hierarchy was also expressed by the extent of domestic animals that a family owned; goats and sheep, along with work hands, tended to manicuring lawn.

The idea of the trimmed lawn first appeared in France in the 1700s, the first lawn mower invented in 1830, in England. Lawn status then became accessible to common folk, and by 1902, again in England, the first mower driven by a gas engine was born. So began the culture of the manicured lawn and the stamp of the colonial world. Since that time, consumers have become seduced into subscribing to a billion-dollar industry that is all about lawns: the result today is that every acre of lawn is an acre of demise of biodiversity within the land environment.

But there’s good news. Slowly the trend is being reversed as noted in the recent announcement—ironically at the birthplace of the lawn mower—of the Royal Horticultural Society awarding a gold medal to a garden full of ‘weeds’ (native plants—the original gardens) at its Tatton Park flower show in Cheshire, England.

The story goes on when we look at the worshipping of the automobile allowing that to forever change a way of life, especially when it came to urban design. The neat row of buildings on the right of Bridge Street that leads to the harbour gave way to the widening of the road to accommodate the car. Where there is an apparent incident happening in the photo lower centre, the large tree behind grew at the end of what was then called Short Mary Street. The tree would eventually be removed and the street opened to connect onto Bridge and to be renamed East Mary Street.

Our love of the automobile and its impact continues with new stores opening in the suburban sprawl of Picton, the trend of offering the visual asphalt assault of the parking lot to the street rather than the option of presenting a human-scaled landscaped building facade to passing traffic is evident. Delegating parking to a main rear entrance and genuinely reflecting aesthetic care of community finesse and also respect in the treatment of the land is something that appears to still be beyond the our realm of appreciation for the land we occupy.

Comments (0)