County News

Above and beyond

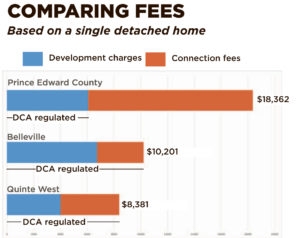

Unregulated connection fees make the County the most expensive jurisdiction to build in the region

Is Shire Hall side-stepping the intent and purpose of the Development Charges Act (DCA)? That is the complaint being lodged by developers in Prince Edward County. They contend that the province established rules and regulations around development charges in 1997, specifically to put order to the patchwork of charges and fees being levied against development at the time. The province did this to make sure municipalities were acting fairly and reasonably, and were charging these fees against growth-related costs rather than replacing existing infrastructure or facilities.

County developers argue, however, that Shire Hall is skirting the intent of the DCA in order to address problems arising from decades of poor infrastructure management and a desperate lack of reserves with which to fund the replacement of an aging and increasingly indebted waterworks system. It is wrong and counterproductive, they say, to saddle new homebuilders with the mistakes of the past.

PLAYING OUTSIDE THE RULES

More than a decade passed before development charges were established under DCA regulations in Prince Edward County. Looking to make up for lost time—and a deep infrastructure deficit—the County went from being a comparatively low-cost place to build to one of the most expensive in the province. But it still wasn’t enough.

Outside of the DCA regulations, the County created new fees to connect to municipal waterworks. In practice, some villages and wards in the County had previously charged connection fees—but in a patchwork way that the DCA was meant to eliminate.

In fact, the stated purpose of the DCA was to make sure these costs are predictable, transparent, cost-effective and responsive to the changing needs of communities. Developers say unregulated connection fees charged by Shire Hall run afoul of these goals.

County officials argue, however, that they are necessary, that costs are rising, the system is in need of capital expenditures and that reserves are dangerously low. They say that somebody has to pay the bills and council figured it couldn’t further burden existing water system customers.

“It’s a balancing act,” said Susan Turnbull, the County’s finance chief. “It’s a difficult balance between developers and ratepayers.”

“It’s a balancing act,” said Susan Turnbull, the County’s finance chief. “It’s a difficult balance between developers and ratepayers.”

But developers argue that simply loading these costs on developers is unreasonable and shortsighted—a practice the DCA was established to eliminate.

“There are no rules governing connection charges in the County,” said Graham Shannon, president of Sandbank Homes.

“It’s a loaded gun,” said Shannon, colourfully describing the predicament faced by developers in the County. “Council can change it at any time. ‘Need more money? Just add more to connection charges.’ In our business, we need predictability and transparency.”

Currently, Shannon sits on a waterworks committee examining rates and considering, among other things, a 50-per-cent hike in development charges.

He points out that a decade ago, about 150 new homes were built each year in the County—roughly the same as Quinte West and Belleville. But since 2008, when development and connection fees were adopted, fewer than 100 new homes have been built annually, while neighbouring jurisdictions continue to build about 150 each year. Shannon calculates this lost tax revenue alone amounts to about $680,000 each and every year.

Turnbull says council made a difficult decision in 2008. Waterworks systems must be funded entirely by the users of the system—either by existing customers or new customers, in the form of connection charges.

“You, too, will have to make a difficult choice,” Turnbull told the committee.

THE BACKSTORY

Development charges and connection fees have a tortured history in the County. When it got around to establishing these fees in 2008, council overshot the market by a wide margin. The County’s consultant, however, assured an apprehensive council of the day that this competitive disadvantage would be temporary—that other municipalities would soon catch up and surpass these rates. It didn’t happen. A confluence of factors persuaded other jurisdictions to keep a tight rein on these charges, mostly in order to stimulate growth in the residential homebuilding sector and in doing so, increase the municipal tax base.

Undaunted, the County pushed on. Even after Shire Hall relented in 2013—discounting some development charges to encourage growth—this municipality remained among the most expensive places to build in the province.

This is because eye-watering connection fees were imposed simultaneously with development charges that were enacted in the County. Connection fees are collected to fund repairs to existing systems and to build reserves to fund replacement.

This would not be allowed under the DCA. Provincial legislation regulates how revenue from these charges can be used. The revenue pays for increased capital costs related to hard and soft services that come as a result of more people and businesses moving into the municipality. For example, the revenue could go toward the construction of new sewer and road systems that might not have been required before.

The County’s connection charge, however, operates outside provincial legislation.

Currently, the municipality charges $12,295 for a new home to be connected to the water and wastewater systems where they are available. It’s not optional. This is in addition to average development charges of $6,067.

Belleville collects $10,201 in development charges, which includes $3,466 for waterworks. Quinte West collects $8,381 in development charges, of which $4,368 is for waterworks. Neither municipality charges an additional, and unregulated, waterworks connection fee.

“Why is Prince Edward County unique?” asked Shannon.

Turnbull responded that the County lost a decade’s worth of development charges—that the deficit has built up and the bills must be paid.

“We didn’t start where everyone else started,” said Turnbull

Comments (0)