Columnists

Glenn Gould and the Last Supper

‘Primo penserio’—brainstorming—first thoughts in a new year bring me to how fortunate we are to have the lending library system that is ours. Libraries are the best of democratic facilities; sources of learning; advocates of literacy and, importantly, they are open and free to everyone. The very existence of libraries is a lesson in giving, in philanthropy. Names like Carnegie and Gates exemplify generosity in action; wealth-sharing that helps guard while encouraging access to information, fundamental in a free world. Libraries are foundations of social development, hubs of enjoyment, and keystones to the betterment of society.

I awaited my turn the other day as both a teacher and a librarian were checking out the various titles members of a kindergarten class—about 20 young minds—had chosen during their visit. There’s a cluster of exuberance as I glance at the titles: Books on spiders and frogs; Dr. Seuss; editions on fish and on stars; there’s Charlie Brown’s Christmas. Whether the books get read over the hubbub of the holidays is not as important as the fact that people at a very young age were being introduced to the concept of the workings of a library. Excitement in their voices told that the experience would likely be retained in memory.

I awaited my turn the other day as both a teacher and a librarian were checking out the various titles members of a kindergarten class—about 20 young minds—had chosen during their visit. There’s a cluster of exuberance as I glance at the titles: Books on spiders and frogs; Dr. Seuss; editions on fish and on stars; there’s Charlie Brown’s Christmas. Whether the books get read over the hubbub of the holidays is not as important as the fact that people at a very young age were being introduced to the concept of the workings of a library. Excitement in their voices told that the experience would likely be retained in memory.

As the little people chatted their way down the stairs heading back to school, it became my turn to check out some reading material that would hold me over for the coming week. I like surprises and to run my fingers through nonfiction at random will generally lead to a few subjects to carry me home.

I love to read and at this time of year, with my woodstove as company, various books plus current issues of the New Yorker or Walrus magazines land in different spots around my house. Thus I spend my days and nights absorbing a string of new pense without ever immersing my hands in dish water, a feat that seems to come easy.

A ten thousand word essay on the advancement of facial recognition technology was an eyeopener. In the western world, Britain seems to be a leader, with the focus of development being with cows. Apparently cows are complacent models as they can be studied with repeated images without seeming to mind. The status of imaging allows for every discrete marking on the head and faces of cows being recorded in fine detail so that along with a bar code tag each cow can be monitored to degrees of accuracy so that supposedly a farmer can manage a herd of three thousand animals as easily as another farmer with a mere one hundred cows. Weight, milk production, birthing, history—all of it pops up on a computer screen to update the status of the animal. When we read about this same idea being developed to facially recognize you and I in a crowd using our drivers licence or SIN card in lieu of bar code, we can’t say that Orson Wells didn’t warn us.

H is for Hawk by author and poet Mary Macdonald is a stunning memoir. A professor of English studies in England she raises and trains a hunting goshawk to console her through deep grief after the sudden death of her father. She is guided by the narrative of a professor from an earlier time, T.H. White, who wrote The Once and Future King and was himself a hawk enthusiast. For me this is some of the best writing and phrasing that I have encountered in a while. The collision of raw brutality of nature with the yearning of a human soul for reconciliation leaves a lasting mark.

Most intriguing in my recent literary travels is a book whose subject is the passion that pianist Glenn Gould exuded in search of the perfect instrument to render his intense musical interpretations. Famed for his recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the read is an intertwining real-life saga of Gould’s comfortable rearing in middle-class Toronto in the 1930s, his on-again off-again relationship with the Steinway Company in New York and Gould’s profound encounter with Verne Edquist a master piano tuner and ‘voicer’ who was of Gould’s same age yet raised in abject poverty on a Saskatchewan farm to eventually acquire the beginnings of his training as a blind person at a then newly founded facility in Ontario.

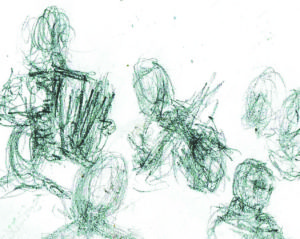

Simultaneously at my bedside is the story of Leonardo da Vinci and his commission to render a fresco of a biblical interpretation of the Last Supper on the walls of the Santa Maria delle Gracie monastery in Florence. Interesting to discover that the space was the lunch room where interns lived in silence and a teacher read from various religious works while the monks or nuns were surrounded by huge tableau on the surrounding walls. The Last Supper was a popular theme, rendered many times in various formats by various artists in numerous locations. Through an intriguing backdrop revealed is Leonardo’s reputation for uncompleted projects, sexual intrigue, and the fact that he was 42 years old when he took on the ‘Supper’ assignment. What captures my attention mostly—I have yet to finish this work and also the Gould story— is how da Vinci carried a small sketchbook on his belt everywhere he went. He used it to take carful notation drawings of human poses in everyday life. He claimed that there were indeed at least 18 basic poses and his curiosity of human form made dissecting corpse a part of his investigation.

Thus da Vinci’s Last Supper stands out for his genius in animating the figures in the work through gesture much like an actor interprets through body language and facial expression without speech. As opposed to the trend of da Vinci’s day where artists used statuary or models to paint the human form, the inspired zest in da Vinci’s’ figures comes from his field notations of posture and expression of everyday bench sitters, street characters, prostitutes, market vendors – a cross section of real life, non-elite inhabitants of the day.

Reading—a good way to launch another year’s episode of our lives. And by the way, I wouldn’t mention this column to the librarian at your local branch as I’m a slow reader and am about to get a call any day now that the titles are overdue.

Comments (0)