County News

The Pity of War

Remembering the 75th anniversary of The Great Escape

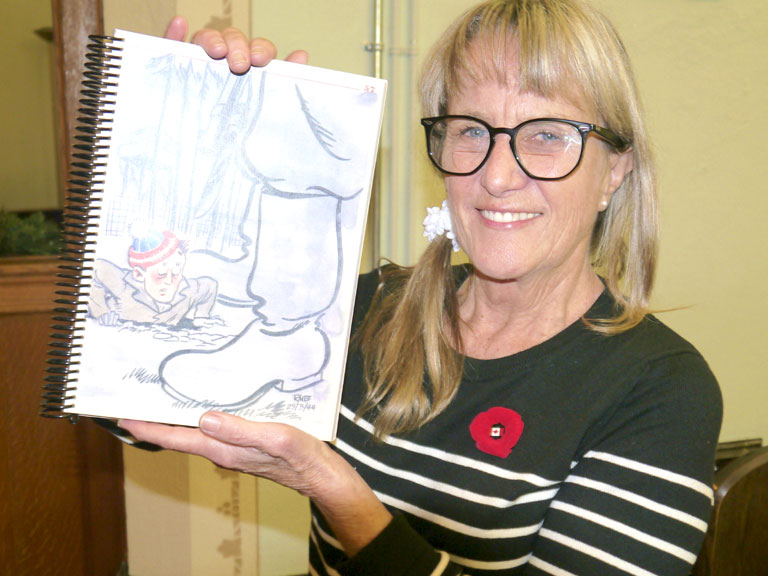

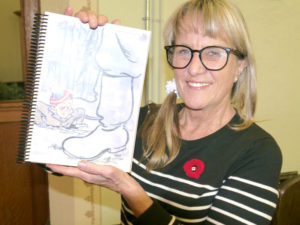

Joan McBride displays a cartoon her father, Robert “Bob” Frederick McBride, drew in his log depicting the moment he was caught escaping the tunnel (dated March 25, 1944).

Every Remembrance Day, St. Mary Magdalene Anglican Church in Picton hosts a special jazz vesper service encompassing a different theme. This year, to mark the 75th anniversary of The Great Escape, Joan McBride developed the program around her father, Flying Officer Robert “Bob” Frederick McBride, the last man out of the tunnel. The service comprised hymns, poetry, storytelling, wartime prose, sing-alongs, prayer, and jazz, courtesy of the Brian Barlow Quartet. “The idea is we take time to reflect on what Remembrance Day is and the sacrifices that men made,” says Joan McBride, program developer.

McBride says people know the story of The Great Escape because of the movie, but notes most of what was depicted didn’t really happen. “What the movie did was put the story on the map,” she says. She describes how her father kept a log, something the Red Cross provided to prisoners of war. “Somehow he managed to bring it with him from Germany,” she says. While the original log is safely stored, McBride had a few reproductions made for family members. “As a child, I was constantly pulling it off the bookcase and peeking into it, because it was a way of finding out about this aspect of my dad that he never talked about, and I was always fascinated by it.” Bob McBride was captured by German troops in November 1942, after successfully beaching his crippled Hampden bomber on the shore of the Bay of Biscay. All crew members survived. He served the remainder of the Second World War as a prisoner of war.

In 2015, Canadian historian Ted Barris published The Great Escape: A Canadian Story. “The story, from the very authoritative research he did, tells us all about the amazing Canadian men and all that they did, and, of course, my dad’s name was in the book,” explains McBride. She talks about how the site of the Stalag Luft III prison camp is now an internationally well-renowned museum. In 2016, McBride and her siblings had an opportunity to contribute to the building of an authentic reconstructed portion of a room in a hut. “That all came about because someone in Warsaw contacted the museum curator to say he had found a set of original bunk beds that were part of Stalag Luft III,” explains McBride.

In April 2018, McBride and husband Charles Morris, visited the museum in Zagan, Poland. “It was just astounding,” she says. “There were certain moments that meant so much to me, and it was very moving.” McBride also felt it was important to bring her father’s log back to where it was originally written, something she was able to do with a reproduction. She describes how her father, as the last man out of the tunnel before they were all caught, drew a cartoon in his log of him coming out of the tunnel and being met by the bayonet. “At the museum, they have a plaque where the head of the tunnel was started in hut 104,” she explains.

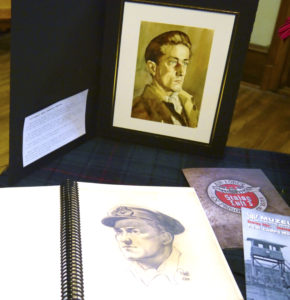

Two very different images of POW Robert “Bob” Frederick McBride: (top) created in 1943 by a fellow POW, and (bottom) drawn by McBride in May 1948.

She describes how when Adolf Hitler had found out 80 men had escaped from this supposedly escape- proof prison, he ordered all those found to be shot. Not all of them were explains McBride. “But 50 were, 23 were brought back to the camp, three actually made it home, and the four found at the mouth of the tunnel, including my father, should have been in the Sagan order (to be shot on sight), but the commandant, who was a Nazi hater, refused to give the four men’s names to the Gestapo. So my father and these three other men’s lives were spared just because of that man.” To further break their spirit, the Gestapo returned to the camp with the cremated remains of the 50 people, as a warning, says McBride. She explains how the men petitioned to have a memorial built for the 50 men, which included six Canadians. “That memorial is still there; we visited it and it is incredible.”

“In our vesper service, The Pity of War, we are reflecting on it and we are trying really hard not to dishonour the people who served,” says McBride. “We are proud of the people, but we regret war, that it had to happen,” adds Morris, rector of St. Mary Magdalene. “It’s a terrible thing that we had to go, and that so many of them had to go and die; we can’t help but be grateful, because the world would be a different place otherwise,” he says.

McBride talks about the photos of the POWs on the wall at the museum, and one that contains her father’s name, yet she barely recognizes him. “My dad was pretty heavy set, but this man, his face was all drawn and thin, and I realized afterwards, that’s what he ended up looking like, toward the end of his time.” We are hoping these services educate and enlighten, and liven people’s lives, and maybe edify says McBride. “It’s important we keep the stories alive.” For information on the Stalag Luft III Museum, visit muzeum.zagan.pl

Comments (0)