Comment

Too many questions

An aircraft lifts off from New York bound for Paris. Passengers settle in for an uneventful flight—despite the likelihood that none knows how much fuel is onboard. Whether it is enough? Or what condition is the plane? When was it last serviced? And by whom? Were they distracted by troubles at home or an irritating supervisor? Have they ever done this before?

An aircraft lifts off from New York bound for Paris. Passengers settle in for an uneventful flight—despite the likelihood that none knows how much fuel is onboard. Whether it is enough? Or what condition is the plane? When was it last serviced? And by whom? Were they distracted by troubles at home or an irritating supervisor? Have they ever done this before?

We put a lot of faith in regulations. In the pilot. The engineering. The maintenance crew. The airline’s track record. We must. Individually, we possess neither the knowledge nor expertise to assess these things on our own. We rely on past performance, layers of regulations and safeguards, as well as loads of oversight, to ensure we arrive safely.

It is how we manage the risk of the unknown.

Shire Hall wants to build about $100 million of waterworks in Wellington to accommodate a predicted four-fold increase in the village population. It is not at all clear that current or future demand for housing will support such exponential growth in the village—nor that many folks currently living here currently see this as a positive prospect. Nor is it clear that County waterworks users across the County are fully conscious of the significant risks being assumed on their behalf. Or that they understand they are wholly on the hook if things go sideways.

The last time the County took on a big waterworks project it didn’t go well. The Picton sewage treatment plant was estimated to cost about $10 million. On paper. By the time Shire Hall got its application ready for provincial and federal funding, the price had risen to $16 million. When final drawings were complete, the cost was pegged at $22 million. The winning bid to build the plant came in at about $32 million— three times the original estimate. It didn’t stop there—cost overruns, contingencies and such pushed the price even higher. Electricity bills are many more times higher than expected. It turns out it takes a lot of energy to push poo uphill.

If a full tally of the cost of the sewage plant on the hill was ever tabulated, it was never released to the public or the media. But it is there—buried in your water bill.

It is an entirely different crew at Shire Hall now. The sewage plant debacle isn’t on them. But this lot is unproven on a project of this scale. Our faith cannot rely on a proven track record.

Despite the wobbly premise envisioned in the Wellington master servicing plan in 2019—the village population swelling to a town of 8,600 people—Shire Hall skipped quickly past the is-this-what-we-want bit. Instead, it went straight to hiring a consultant to calculate how to divide the massive waterworks investment between the new and the existing users. Full marks for exuberance and enthusiasm. But it all seems too much, too soon. Abandoned cart, no sign of a horse.

Nevertheless, Watson and Associates will present its updated findings tomorrow (Thursday, May 13) to a committee of council. It includes a draft by-law and a checklist guiding council across the finish line: approve the study, determine that no further meetings are required and then pass the by-law. It could all be done in a matter of weeks.

Strap yourselves in. It’s going to be a bumpy flight.

While Shire Hall has offered a veneer of stakeholder consultation in the tick-the-box manner of public engagement, there remain too many questions. Too many moving parts. Too many assumptions. It is too much for Shire Hall and council to take on without a more direct, fulsome, and ongoing involvement with the folks who fund this enterprise. The risks are too many and too profound.

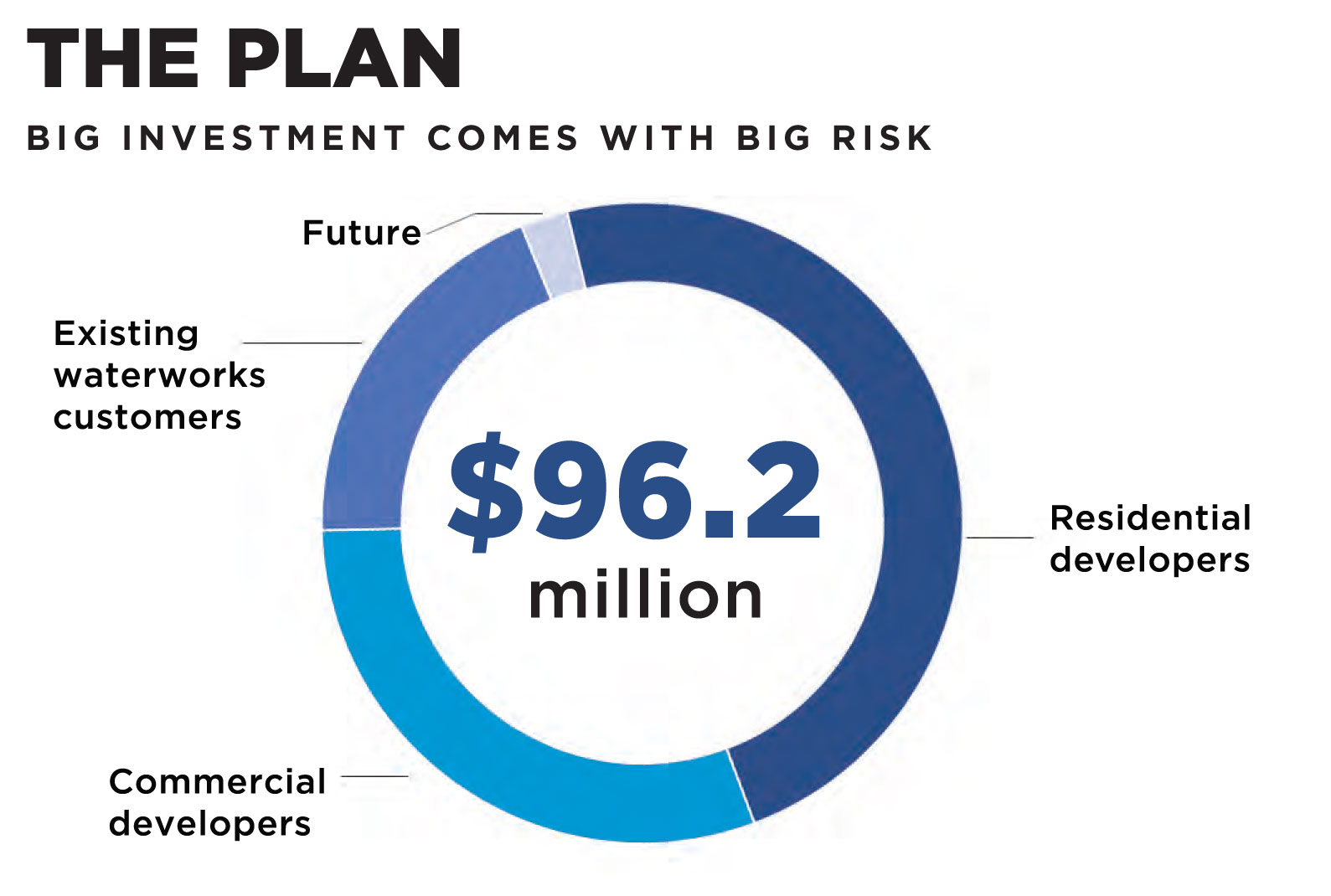

According to Watson’s study, about three quarters, or about $75.5 million, of the projected $100 million investment is potentially recoverable by way of development charges—earned from the sale of new homes and commercial buildings. (Potentially being the keyword here.) Existing waterworks customers are on the hook for about $18.5 million—that is an investment that will enhance the system for current Wellington waterworks customers, including boosting water pressure and prolonging the viability of the overall system.

But the risk exposure to existing waterworks customers doesn’t stop at $18.5 million. While $75.5 million may be recoverable—in theory—there can be no certainty how much will be collected. Shire Hall is set to spend about $70 million on Phase 1 over the next three years. Every dollar that Shire Hall invests and subsequently fails to collect from developers must be carried by existing waterworks customers. Forever.

To offset this risk, Shire Hall is negotiating with developers to secure a portion of the $75.5 million upfront in exchange for certainty regarding when developers can connect to this system—and sell their homes.

This is a good thing. But less of a good thing than it appears. Of the $75.5 million Shire Hall hopes to collect in development charges for this project, just $46.3 million is recoverable from residential development—that is, new homes. How much they will commit upfront remains unclear.

But we know that fully $29.2 million is expected to come from commercial or non-residential development. Here it gets really hairy. The plan assumes a build-out of nearly a million square feet of new commercial development. To understand the audacity of this assumption, consider that the new grocery store in Picton comprises about 32,000 square feet. It would take 29 buildings of this stature to reach the plan’s target.

Bear in mind, too, that the last truly new commercial development in Wellington was the Tim Hortons and gas bar—together about 3,800 square feet—was built in 2015. Before that was the liquor store (5,000 square feet) and the Dairy Bar (3,000 square feet) in 2012. Wellington’s track record (12,000 square feet in a decade) suggests that commercial developers aren’t exactly burning down a path to Wellington’s door. At this pace,it will take more than 700years to amass the commercial development in the village imagined in the plan.

But it gets weirder.

Incredibly, prospective commercial developers will be asked to pay the highest commercial development charges of the 12 jurisdictions Watson surveyed. By a wide margin. Amazingly, the Wellington specific development charge means that a commercial developer will have to weigh spending $34 per square foot in development charge in this village versus about $10 in Picton, Rossmore or Bloomfield. It seems utterly implausible that any developer would spend an extra $1.2 million in development charges on a 50,000 square foot commercial building to do business in Wellington versus one of our neighbouring centres—let alone enough of them to construct a million square feet of commercial in this village.

So if these folks aren’t coming—who pays their share of the infrastructure investment? Well, Shire Hall has shrewdly inserted a bit of a safety valve in the plan. About $30 million—of the $100 million required by the master servicing plan—is being put on the shelf for the time being. If circumstances change or the market cools off—or commercial development fails to materialize—that phase can be extended, delayed, or scrapped altogether.

The plan relies, then, on seeing a vast and rapid expansion of new homes in Wellington. It means 2,591 new homes over the next two decades in this wee village. It is a big ask.

It is not as though we will crash into the ocean if this infrastructure plan goes awry. No one is likely to die or suffer injury. It is just money. Your money. And this place gets a bit less affordable.

A long term plan shouldn’t be based on a spike in the data…