County News

Wellington’s Winter Heroes

Two daring ice rescues a century ago cemented Murphy and Ingram’s place in village history

One hundred years ago this month, two Wellington men—Gillis Ingram and Dayton Murphy—carried out a rescue so daring it has become part of local legend. It is now up to Ingram’s granddaughter Kathi Pickard to share the story with a new generation.

On February 21, 1926, 21-year-old George Deering wrapped up a fishing excursion and was bound for the mainland. But as he made for Hyuck’s Point, shifting pack ice trapped his small boat and carried it eastward in a grinding ice jam. Repeated attempts to reach the stranded fisherman failed as his vessel drifted farther from shore. Night fell. He was in deep trouble.

Telephone lines lit up as residents tried to rouse a rescue team. But outside assistance would not arrive in time. The rescue would have to be made by local men.

At 11 p.m., on a bitterly cold February night, Murphy and Ingram pushed off in a small skiff. Their method was as ingenious as it was dangerous, according to Pickard.

Using a pair of ladders laid across the ice pack, the makeshift platform enabled the pair to distribute their weight. One wrong move and they would be captured by the frozen lake. Balancing themselves on the ladders, they pushed the skiff through the ice a few feet at a time. They would climb into the skiff, reposition the ladders and repeat.

Slowly, painfully, they edged their way toward the exhausted Deering. When at last the pair reached him, Ingram and Murphy pulled themselves and their rescued passenger back to shore along a rope they had paid out behind them on their outward journey.

The feat was all the more remarkable because Ingram had recently suffered a broken arm.

It would not be their last.

Nine years later—another cold February—Murphy and Ingram were again called to brave the frozen waters of Lake Ontario.

Two boys, aged 12 and 16, had fled a children’s shelter in Belleville and attempted to cross the “big lake” on a homemade raft. The desperate gamble turned into a 26-hour ordeal as they drifted helplessly in icy waters. In a dramatic scene, packages of food and supplies were dropped to them from a Royal Air Force plane, keeping them alive while rescue efforts were assembled.

Murphy and Ingram loaded a 16-foot, leaky skiff with ladders, poles, rope and grappling hooks and launched from the shoreof the village. Slushy, heavy ice blocked their path. Again, they used ladders to traverse the ice pack surface like snowshoes—dragging their boat behind them.

At last, they reached the boys.

Darkness was falling as the heavily burdened skiff — now carrying four people, two heavy ladders, equipment and the parcels dropped from the plane—began the return trip. The boat was leaking badly and had to be bailed continuously.

As the motley crew neared shore, a swift current churned with jagged chunks of ice. Murphy and Ingram threw a grappling iron repeatedly until it caught. The final struggle through the current was the hardest yet. Spectators on shore, at last, seized their line and pulled them to safety.

Everyone arrived back on shore. Safe.

RECOGNITION

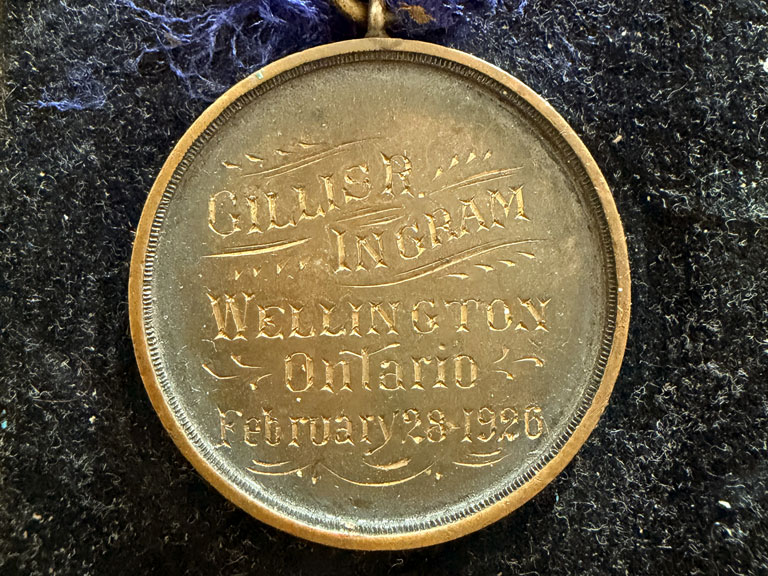

The courage of Murphy and Ingram soon became part of the local story. For their first rescue, both men received medals of bravery from the Royal Canadian Humane Society.

Following the second rescue, each was awarded a bar to add to his lifesaving medal — the decorations inscribed with his name and the dates of his extraordinary deeds. Ingram was also given a gold locket and watch for his bravery.

Gillis Ingram’s life of service extended well beyond those frozen nights on Lake Ontario.

Ingram began his military service remarkably young, serving as a corporal in the 16th militia at just 13 years old. He later enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, serving overseas during the First World War, including postings in Serbia and Russia—where Canadian forces remained until 1919—and later assignments in China and Japan.

During his service abroad, Ingram was said to have helped smuggle a young Russian prince and his nurse into Japan amid the upheaval following the Russian Revolution. He was placed on reserve in 1940.

At home in Wellington, Ingram was known not only for his wartime service but as a fisherman, a carpenter, and later a police officer.

He married Inez Bovay, and together they had one son, Elwood “Tweet” Ingram. He was just six days old during the first rescue.

The heroes take a photo with the two boys they rescued. (L-R): Dayton Murphy, Charlie Weaver, Henry Vardy and Gillis Ingram.

Comments (0)